“Art is my weapon”: Looking at James Luna

Words by the editor, Myfanwy Greene

I remember when I first encountered James Luna’s triptych ‘Half Indian/Half Mexican’ as I wandered through the galleries of The Brooklyn Museum. I was struck not only by the sheer size of the piece, which towered across the other portraits in the gallery, but by Luna’s intimate gaze, his stoic expression, and the gentle confrontation of the piece. The piece is reminiscent of mugshot photography, a commentary on the way non-white American bodies are policed and surveilled. And yet, the portrait is utterly beautiful, inviting the viewer to look at Luna closely and with care. Equally, it is a commentary on Luna’s dual heritage, examining both parts of his identity. It was difficult to pull my eyes off him, the portrait demanding an attention with which I was unfamiliar. James Luna examined me as I examined him, and it was this feeling of profound connection that has led me to research him further.

‘Half Indian/Half Mexican’, 1991, silver gelatin print, 60 x 144 inches.

Pictured in the installation Towards Joy: New Frameworks for American Art at The Brooklyn Museum, 2025.

‘Half Indian/Half Mexican’, 1991, silver gelatin print, 60 x 144 inches.

© Garth Greenan Gallery

James Luna (1950-2018) was a Payómkawichum/Luiseño/Ipai (Native American) and Mexican artist from California, most famous for his performance pieces, photography, teaching and activism. His art was dedicated to both undoing and revealing the racist stereotypes towards Native Americans and Mexicans prevalent in American culture and art. Luna particularly critiqued the ‘selective romanticisation’, as he called it, of American Indians in hegemonic American society, revealing this hypocrisy in performance works like ‘Artifact Piece’ (1987-1990) and ‘Take a Picture with a Real Indian’ (1991, 2001, 2010). Luna used humour in many of his works, and this was undoubtedly an effective means for revealing the more insidious sides of American culture and white Americans’ relationship to the Native.

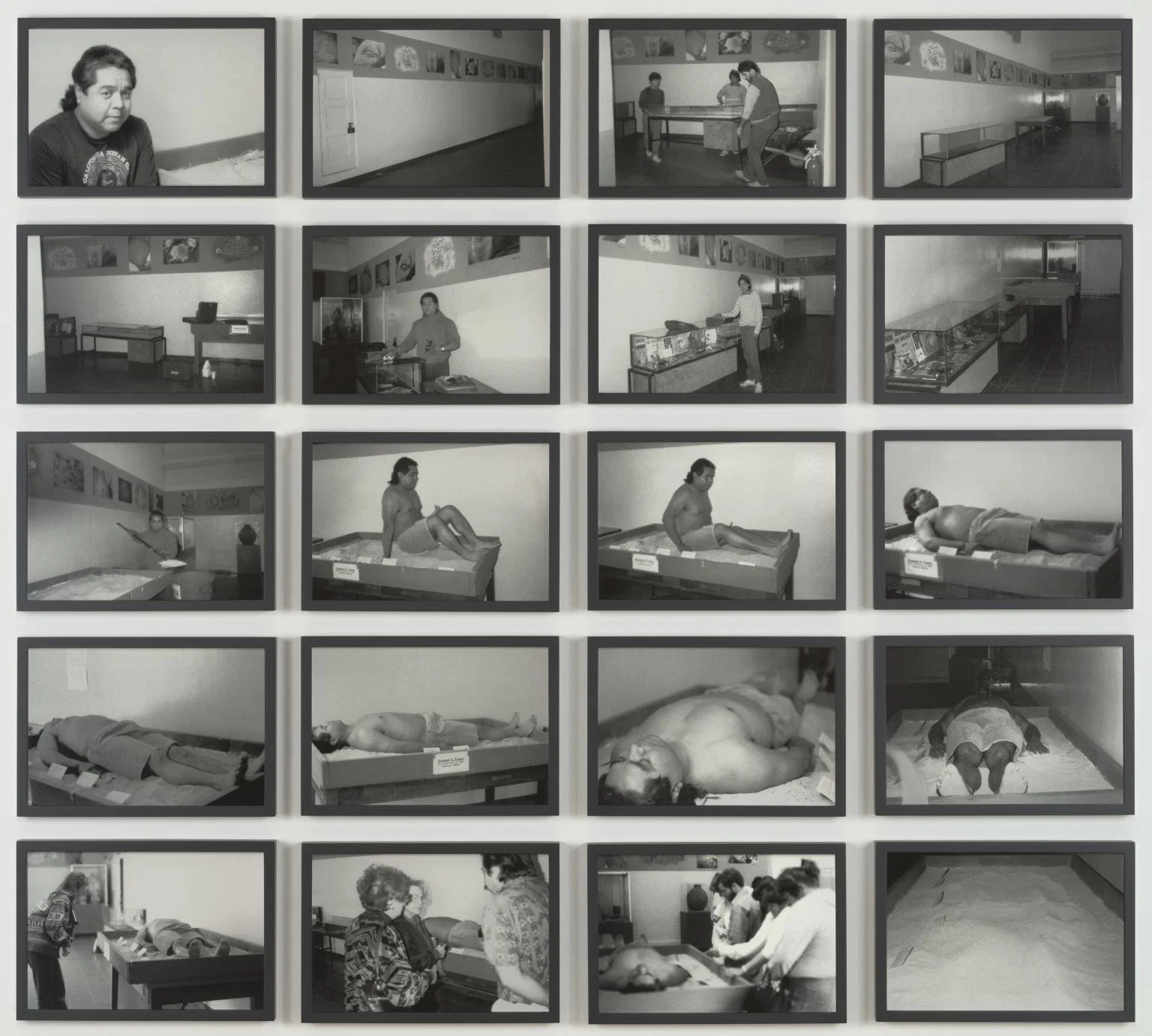

‘Artifact Piece’, 1987, performance piece and mixed media.

© Tate

In ‘Artifact Piece’, first performed in 1987, Luna lay himself in a display case, face up, surrounded by labels. The labels denoted his scars, and he was also surrounded by personal objects from his life like his college diploma, some divorce papers, photos from his family life and even his favourite music, in the form of records and cassettes. This piece touched on many pertinent themes regarding the display of Native bodies and histories in the institution of the American museum. The fetishization of the Native body and its coding as exotic and inhuman were brought to the fore, as Luna highlighted the lack of autonomy, agency and power that Native artists had over their image, heritage and self in the spaces of white institutions. Jean Fisher argued that ‘Artifact Piece’ revealed the ‘necrophilous codes of the museum’, a disturbing revelation about the purpose of Native bodies in American institutions. It is as if the deceased Native body was of greater worth and greater value than the live, autonomous body. ‘Artifact Piece’ was a brave and uncomfortable work that Luna himself struggled with. In an interview with Richard Hill, Luna revealed that he may never have conceived of/performed the piece had he known how horrible it felt to just lie in the case and be examined. Through ‘Artifact Piece’, Luna critiqued the exoticisation and fetishisation of Native American bodies, stripped of voice and autonomy by the American institution, bodies to be leered at and drooled over, rather than listened to and understood.

‘Take a Picture with a Real Indian’, 1991, polaroid, 16 x 192 inches.

© Garth Greenan Gallery

Another key performance piece was ‘Take a Picture with a Real Indian’, which Luna described as a process of ‘mutual humiliation’. In ‘Take a Picture’, Luna made himself into a tourist attraction, inviting crowds of people to take photos with him as he stood, stoic, in his place. Here, then, was another example of the ways in which the Native was commodified, romanticised and ogled at by the American public. He famously re-performed the piece on Columbus Day in 2010, to much the same effect as his first performance in 1991. The Garth Greenan gallery wrote, on ‘Take a Picture’, that the shallow excitement of the tourists paired with the inauthenticity of their encounters with Luna revealed how much of the American public continue to see Native Americans as folkloric, romantic figures, devoid of any real, palpable, lived experience of Americanness and its culture.

‘We Become Them’, 2011, chromogenic print, 60 x 96 inches.

© Garth Greenan Gallery

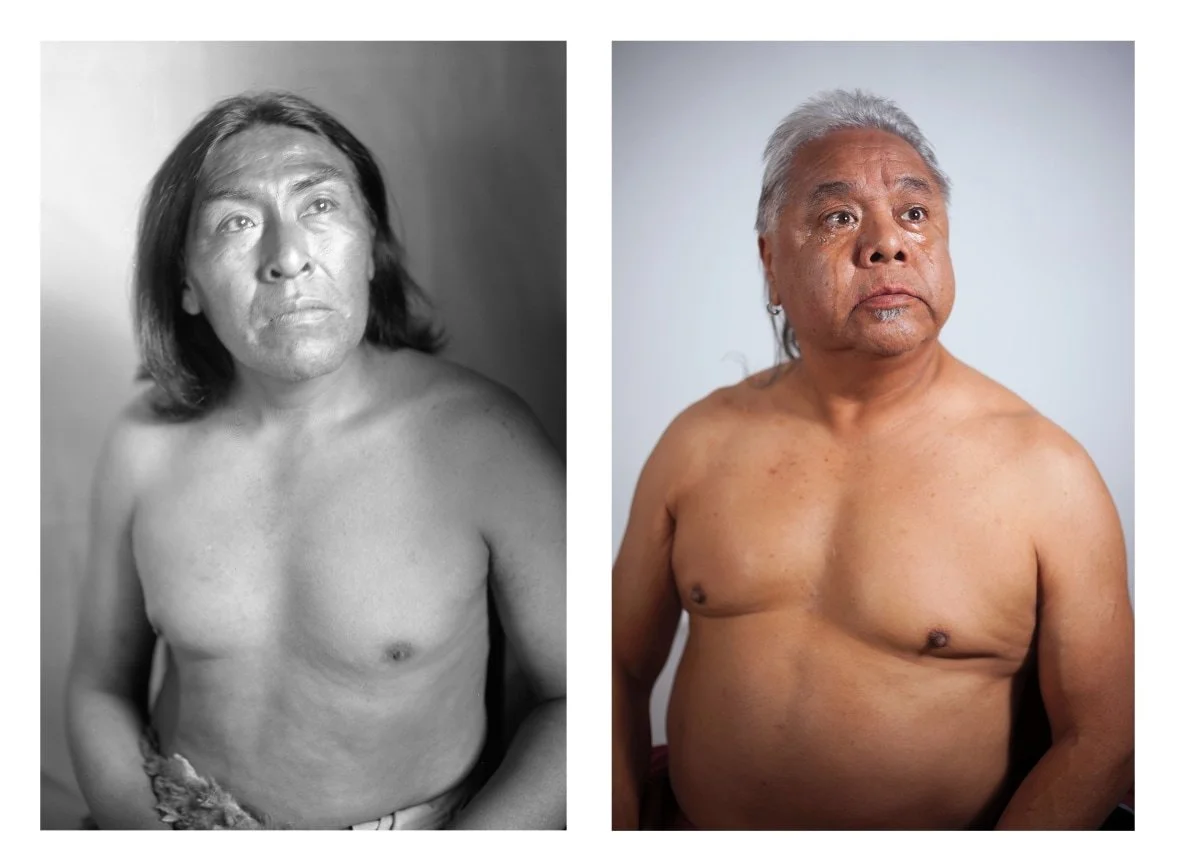

Luna is as playful as he is political (the two are hard to divorce in his works). In ‘We Become Them’, Luna takes Indigenous masks and replicates them in portrait. This doubling is both comical and clever, as Luna reconciles the traditional with the modern Native face. Another example of doubling in his work is found in the piece ‘Sometimes I Get So Lonely (Ishi)’. A much less comical portrait, Luna places himself alongside a portrait of a Native American man. Both stare into the top right of their respective portraits, wistful, forlorn expressions on their face. Luna has tears streaking down his face. The two men are bare-chested, giving the portraits a raw, corporeal nature, again asking the audience to consider the ways in which we are used to seeing and experiencing the Native body. This work challenges the notion of the Native American as an unwavering, unfeeling warrior, providing the men with a tenderness that draws attention to their humanity. It is a particularly emotive, visceral piece that reminds us of the erasure of the Native population, their forced displacement, and the ways in which American settlers attempted to dehumanise these people so thoroughly. Luna re-humanises both the Native man, providing the space for feelings of loss, nostalgia and outrage at the displacement and eradication of Native peoples.

‘Sometimes I Get So Lonely’, 2011, chromogenic print, 60 x 48 inches.

© Garth Greenan Gallery

Right up until his death Luna was making distinctly activist art. ‘Make Amerika Red Again’ satirizes the MAGA hat, pointing out the hypocrisy in the Trumpian slogan which fails to admit the dark, colonial past of American democracy and nationhood. Using traditional Native bead designs and a yellow feather, Luna has created a work that recalls Native headdresses. The bold red, white and yellow skews the colour scheme of the American flag, again, perhaps a comment on the erasure of Native/non-white cultures in the America of today, particularly in the political sphere. The piece’s title also calls attention to this erasure, and the reclamation of the pejorative ‘red’ to describe Native American skin makes for a powerful message.

‘Make Amerika Red Again’, 2018, mixed media, 5 x 6 x 10 inches.

© Garth Greenan Gallery

Unwavering in his commitment to art as activism, James Luna was an artist who changed the way in which Native American/Mexican artists were viewed and challenged the hegemony of the American institution. We have much to learn from him, now and in the future. He will continue to inspire for generations to come.

—————

Sources:

Richard William Hill, “Remembering James Luna (1950–2018).” Canadian Art, https://canadianart.ca/features/james-luna-in-memoriam/.

Note 1: Title quote is a segment from the quote in “I’m an activist, an art activist.

Art is my weapon of choice.” Geraldine Ah-Sue, “Speak to the Unspeakable: James Luna and Geraldine Ah-Sue in Conversation.” Open Space, May 17, 2018, https://openspace.sfmoma.org/2018/05/james-luna-and-geraldine-ah-sue-in-conversation/.

https://www.moma.org/artists/34698-james-luna

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/luna-the-artifact-piece-l04879

https://www.garthgreenan.com/artists/james-luna

Images credit to The Garth Greenan Gallery, NYC and Tate, London.