Interview with Clare Durham, Auctioneer & Ceramics Expert

Words by Georgina Way

Edited by Myfanwy Greene

There aren’t many people with whom you can pick up the phone and have a long conversation about a variety of subjects including (but certainly not limited to) bestselling teapots, the issues surrounding CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), aesthetic versus academic collectors, the dying art of communication with the occasional cat interruption…

Clare Durham is one of the very few. As well as being expert in British and Continental ceramics and an engaging and adept auctioneer, she is one of the kindest and funniest people I know. Conducting an interview with her was pure joy.

After working at Woolley & Wallis Auctioneers as Head of the Ceramics Department for eighteen years (having managed their Press & Publicity for a prior six years) Clare recently moved to Henry Aldridge & Son, and I wanted to take this opportunity to ask her some questions not only regarding her area of expertise, but also her perspective on the art auction world and the challenges she has faced navigating the sector. Needless to say, she gave me many thought-provoking answers.

Clare Durham, Auctioneer and Expert in British & Continental Ceramics.

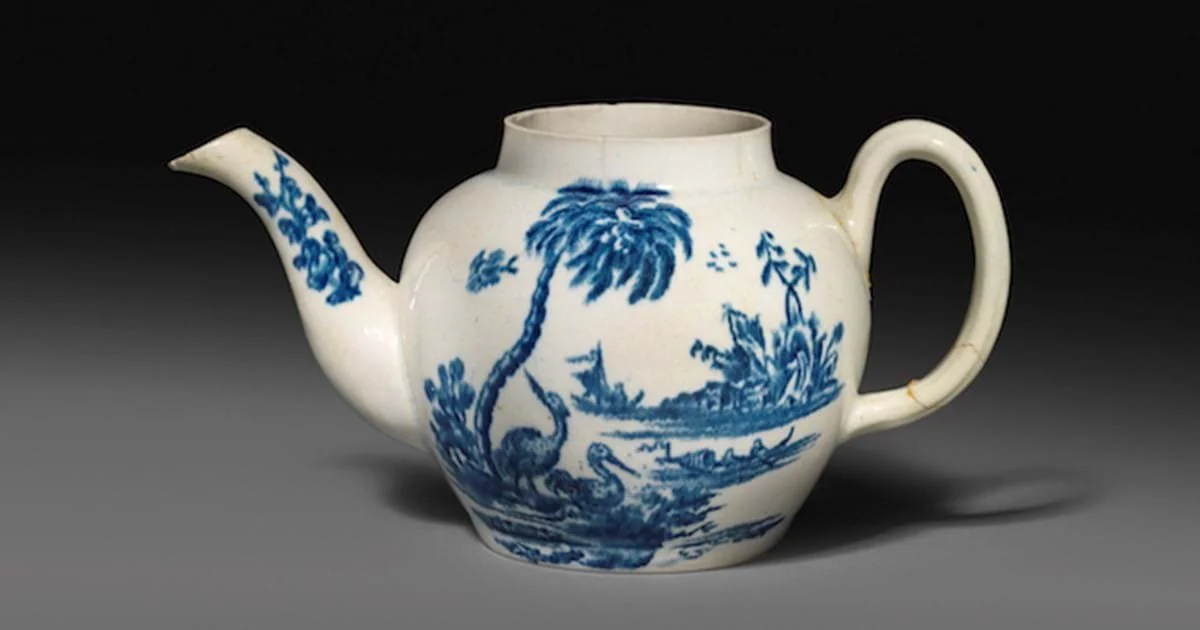

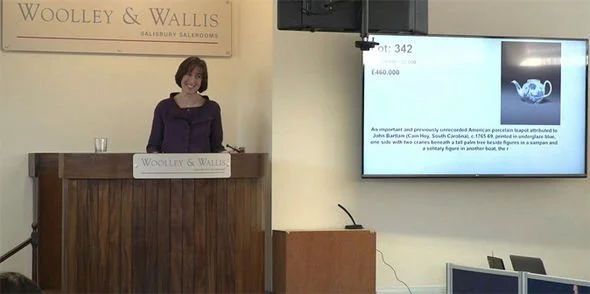

After a few minutes of catching up amidst volleys of giggles, we settled down to business. I wanted to start off by asking her about the John Bartlam teapot which she sold to The Metropolitan Museum of Art for £460,000 in 2018. The teapot itself, cracked and missing its lid, was not her focal point.

Instead, Clare drew attention to the importance of fostering excellent relationships with her clients, both vendor and buyer. What can often be forgotten about the auction world is that it is an industry which requires sensitivity and empathy. Frequently, people may choose to do business with an auction house as the result of a bereavement or other difficult circumstance, and it is the understanding nature of the auctioneer which can really make all the difference.

An important and previously unrecorded American porcelain teapot attributed to John Bartlam - image courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

In the case of Bartlam teapot, Clare explained how it was the highly charged, high-pressure circumstance (the fact that the teapot’s significance was not previously recognised) that created a symbiotic relationship, as the teapot was so highly valued by auctioneer, vendor and seller alike.

Trust, Clare said, is a fundamental part of the role. Clients entrust you with not only the artefact itself, but also its emotional value and history. This led me to ask Clare whether clients felt more at ease with a female valuer.

Yes. On the whole, she believed that it is generally easier for women to be sympathetic and responsive towards charged emotions than it is for men (due to the way in which we are all societally conditioned, regarding gender at birth, to behave). This highlighted the importance of having a balanced valuation/auctioneer team.

Had she ever experienced any form of sexism or been victim to patronising male figures of authority? Yes, especially in the early noughties, when the auction world was still a predominantly male space. When Clare joined Woolley & Wallis, there were no female heads of department. By the time she left, there were four.

The moment the hammer went down on the Bartlam teapot, sold for £460,000.

At this point in the interview, there was a scuffle, a squawk and Clare briefly turned away to reprimand the cat who had been nibbling her toes. With an aggrieved mew the cat slunk away and our conversation continued.

I wanted to hear Clare’s view on the moral arguments which surround not only the auction world but the art world in general, namely, the aesthetic vs. academic collectors debate, CITES and private vs. public collections. CITES is the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, a international agreement to regulate or ban entirely the international trade of artefacts (like ivory) regarding endangered/threatened species across the globe.

As Clare said, the only real answer to all of them is that every case is individual and subjective; it just totally depends. Take CITES for instance. By banning the sale of items with ivory or rhino horn, do we run the risk of erasing traditional cultural practices and some communities’ heritage? Is it right to do so? There has yet to be any evidence to suggest that controlling the antiques market has reduced modern poaching. There have been numerous legal battles focusing on an item with ivory and/or horn, often resulting in that piece being hidden away, unable to be sold or kept.

Surely, I query, it is better for items to be on display somewhere where they can be appreciated for their craftsmanship? The same applies, slightly less rigorously, to marine ivory. Items originally intended to be used as tools, and carved with exceptionally fine detail, are now occasionally perceived as offensive. And yet, it could equally be argued that these very items are examples of historic tradition and way of life which is rapidly vanishing from history, as a result of these contemporary beliefs.

An Inuit Arrow Straighter, walrus ivory in the form of a caribou. Image taken by author, courtesy of Woolley & Wallis.

On the subject of displaying items, I asked Clare whether she thought it better to sell items to private or commercial collectors. Her answer was whichever provides the greatest pleasure.

If an item is bought by a museum, but then only kept in the archives, would it not be better if it was bought by a private collector who would be able to display and enjoy it? This was one of the advantages of the increase in online and telephone bidding, she explained. The rise of technology has deconstructed the patriarchal hierarchy of auction houses. Although new technologies has greatly and permanently damaged the trade hierarchy, it has also enabled private collectors to bid on items without feeling intimidated by the professionals.

Has technology helped or hindered the landscape? Clare paused to consider and answered that, although technology has made artworks in general more visually accessible, it has also contributed to the decline in detailed knowledge and the love of learning. When I asked her to expand, she explained that, by having everything so readily available online, it has made it harder for people to actually engage with a piece, be that coming down to viewing at auction houses or meeting and talking with experts.

An auction house is a fantastic place for someone just starting out to learn. It is an ever changing museum where you can handle rare and beautiful objects. The advent of technology has made people lazier, and the rise of social media and an increasing interest in the ‘aesthetic’ has resulted in people buying what they deem prettiest, rather than the necessarily most interesting.

Unfortunately, this was where our time ran out, and I felt as though I’d only just scraped the surface. For every question answered, I had a dozen more. It had been a fascinating conversation about the art auction industry, a less well known aspect of the art world.

You can watch the sale of the teapot here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o4kTYwGqd60.