Jazz in Art: Rhythm, Colour and Movement

Words by Charlotte Whitehill

Edited by Myfanwy Greene

Inspired by our recent Norman Rea Gallery x Hard Magazine Jazz Club Winter Formal, I found myself thinking about how jazz has shaped art. Emerging in the early 20th century, movements such as the Harlem Renaissance, Synchromism, Futurism, and Abstract Expressionism drew on the syncopations and improvisations of jazz to develop a visual language. Artists transformed sound into colour, rhythm into form, and musical experimentation into new modes of artistic expression.

Jazz is a cultural force. Emerging from African American communities in the early 20th century, it became a vehicle for expression, liberation and resistance. In particular, it gave a voice to those facing racial oppression. Its musical characteristics found parallels in modern art, which was simultaneously embracing experimentation and a break from artistic tradition.

The idea of visual syncopation became crucial; artists sought to replicate the structure of jazz in their use of colour, line, and composition. Just as jazz musicians disrupt expected rhythms, artists disrupted traditional forms of art to generate movement and dynamism. Jazz shaped and inspired the aesthetics of so many modern art movements.

Following World War I, jazz travelled from New Orleans to cities such as New York, Chicago and Los Angeles. It became a symbol of a new cultural modernity, marked by interracial relations, nightlife, urban energy and rebellion against norms. Modern artists responded by trying to capture the speed, pulse and motion of contemporary life. Jazz was not background music; it was a cultural shift that inspired an artistic response.

This cultural shift began with the Harlem Renaissance, which emerged alongside the Great Migration, the period when thousands of African Americans relocated from the American South to the North, in search of better opportunities and distance between them and the horrors of their enslaved pasts. Harlem, New York, became a vibrant centre of Black intellectual and artistic life. Musicians, writers and visual artists sought to redefine African American identity, celebrate Black culture and challenge racist stereotypes through art, music and literature.

Aaron Douglas, ‘Aspects of Negro Life: Song of the Towers’, 1934. Oil on Canvas. New York Public Library.

One of the most iconic jazz-inflected artworks of the Harlem Renaissance is Aaron Douglas’ ‘Song of the Towers’ (1934) from his ‘Aspects of Negro Life’ mural. The painting shows a saxophonist standing on top of a giant gear, his music radiating outward in circular rhythmic beams of light. Douglas’ use of sharp, strong silhouettes, combined with his geometric layering and bold colour fields, creates a visual equivalent of jazz’s syncopated rhythms. The saxophonist symbolises mobility, freedom, and expression, which jazz offered African Americans in the early 20th century. With its upward movement and spiralling forms, the artwork captures both the optimism and hope that people held for the new century, while simultaneously commenting on the struggle embedded in modern Black life in America.

The Harlem Renaissance would decline, but its cultural impact persisted. It cemented jazz as a foundation of African American identity and confirmed its influence on visual art and artists.

Shifting to the Synchroism, which, although it is not directly tied to jazz, still aimed to paint with colour. The movement asserted that colour could function like musical scales, harmonies, and rhythms.

Morgan Russell, ‘Synchromy in Orange: To Form’, 1913-14. Oil on Canvas, 135 × 121 1/2 x 1 1/2 inches. Collection Buffalo AKG Art Museum.

A key example is Morgan Russell’s ‘Synchromy in Orange: To Form’ (1913-1914). The painting features multiple prismatic planes of orange, green and blue that trick the viewer’s eyes into seeing it rotate and pulse like the music. Its rhythmic colours anticipate the improvisational structures of jazz that would take hold later in the 20th century.

Although created before the jazz age fully evolved, Synchromism provided the theoretical groundwork for thinking about art musically, using colour as vibration, form as rhythm and composition as harmony.

The Futurism movement similarly embraced the speed and noise that aligned perfectly with jazz's energy and, although it also predates jazz’s popular explosion, it remains an embodiment of the necessary qualities. Futurist painters sought to depict the sensation of movement itself, using fractured forms, diagonal lines, and repeated shapes to suggest momentum and rhythm.

Giacomo Balla, ‘Abstract Speed + Sound’, 1913-14. Oil on unvarnished millboard, 54.5 x 76.5 cm. Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

Giacomo Balla’s ‘Abstract Speed + Sound’ (1913–14) also visualises that velocity through sharp angular lines and patterns that mimic vibrations. Viewing this work through the lens of jazz, it almost feels like a visual translation of percussion, with its chaotic compositions. Futurism’s obsession with dynamism created a visual vocabulary that later aligned with the spontaneity of jazz. As jazz continued to spread internationally across Europe, many artists embraced it as the musical embodiment of their ideas.

By the 1940s and 50s, jazz had become integral to Abstract Expressionism's identity, especially within New York’s art scene. Artists gathered in jazz clubs where bebop musicians like Charles Mingus performed at fast tempos and with complex chord improvisations.

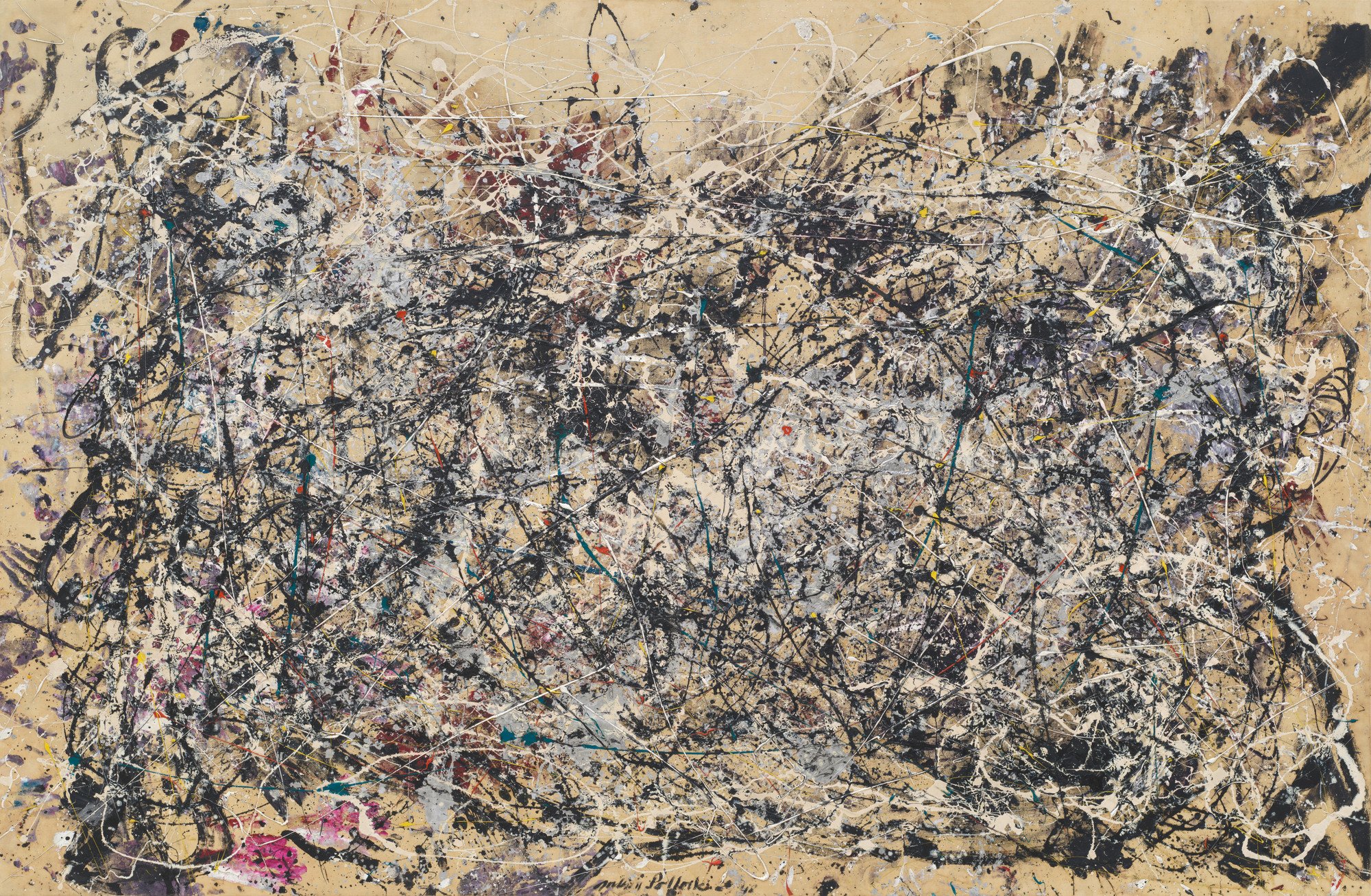

Jackson Pollock, ‘Number 1A, 1948’, 1948. Oil and enamel paint on canvas, 172.7 x 264.2 cm. New York City, The Museum of Modern Art.

Jazz embodied freedom, individuality and risk, qualities that Abstract Expressionists also strived to showcase. Jackson Pollock emphasised the connection between visual art and how jazz music inspired the movements. His piece ‘Number 1A, 1948’ displays webs of dripped and poured paint, forming a complex structure that mirrors the rhythmic improvisation of jazz. Pollock’s method of moving physically around the canvas creating his bold and spontaneous paint strokes ultimately echoes the improvisation of jazz performances. In this instance, the canvas becomes a stage, with Pollock as the performer.

Across the 20th century, jazz shaped what artists depicted and how they also thought about art. It offered a new aesthetic built on rhythm, improvisation and emotional intensity. From the silhouetted musicians of Aaron Douglas to the swirling abstractions of Synchromism and Futurism and the gestural improvisations of Jackson Pollock, jazz transformed modern art into a visual language of movement. Today, those visual syncopations remain embedded in culture, and continue to remind us that art and music are deeply intertwined.

Very fittingly, that same energy, rhythm and elegance infused our Winter Formal last week. Thank you to everyone who joined us! We hope your night was every bit as jazzy as the art that inspired it.