Cadeirio'r Bardd and the Bardic Chair

Words by Milly Evans

Edited by Myfanwy Greene

The eisteddfod is a traditional Welsh festival focusing on literary and musical talent celebrated annually in Wales. To many of us who grew up in Wales, we think of being in primary school, making Welsh cakes, memorising poems and writing our own. In my school the winner of the poem competition was crowned the ‘Bard’ and had to get up in front of the whole school and sit in a very grand wooden seat, and this seemingly strange ritual was never explained to us, especially as the winner of the musical competition received a normal modern trophy. My delve into the history of the mysterious wooden chair revealed a more prestigious and glamorous award than my primary school sticky-floored canteen ceremony initially had me believe.

Eugene Van Fleteren, [Detail from] Gadair ddu, 1917.

Dating back to 1176, Lord Rhys held the first eisteddfod and awarded a place at the Lord’s table to the people he deemed best poet and best musician. This developed through the years and by the late 19th Century, when the modern eisteddfod was established, chairs were commissioned specifically for this annual ceremony. It is known as Y Gadair Farddol (‘The Bardic Chair’) and the ceremony Cadeirio’r Bardd (‘the chairing of the bard’). The chairing of the bard is the most anticipated event of the whole eisteddfod.

Eugene Van Fleteren, [Detail from] Gadair ddu, 1917.

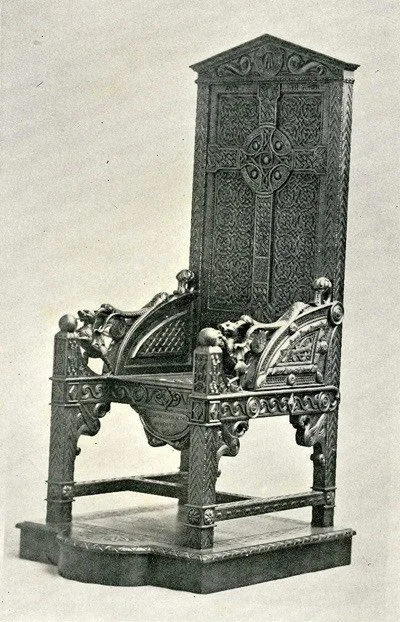

The chair used in my primary school undoubtedly dated from the 1960s and was dragged out of the back of storage cupboard, but the real gadair farddol is much more intricate, and its origin fascinating. Every year a new chair is carefully designed and created by wood-carvers. One of the most famous bardic chairs is the 1917 gadair ddu (‘black chair’). Due to an untimely passing in combat six weeks prior to the festival, the Prifard (‘main bard’) was awarded posthumously, and so instead of the cadeirio’r bardd, the chair was draped in black cloth and therefore became the ‘Black Chair’. Interestingly, this famous piece of Welsh history was not created by a Welshman, but instead by a Belgian refugee. Eugene Van Fleteren was a wood-carver, who was displaced to Wales during World War One. Van Fleteren made multiple artistic contributions to Eisteddfodau, including the 1918 Bardic chair, and certificates for the children’s Eisteddfod. Van Fleteren’s work is stunning, well thought-out and complex, finished with multiple culturally significant symbols. My personal favourite feature of the gadair ddu is the Welsh dragons on the armrests.

Eugene Van Fleteren, [Detail from] Gadair ddu, 1917.

Sadly Van Fleteren’s displacement during World War One was not uncommon, as many other Belgian refugees came to Wales. There were plenty of vacancies in coastal houses and hotels in particular, and the story of a small country invaded by a larger one resonated with the Welsh. There was already an existing Belgian community in Wales, with copper and zinc workers in Swansea and Belgian nuns in a convent in Rhyl. Among these was Emile de Vynk, who was offered refuge along with his wife and daughter during World War One in a coastal town in North-West Wales. De Vynk carved the Bardic chair for the 1923 Eisteddfod, held in the Northeast Welsh town of Mold.

Emile de Vynk, Bardic Chair, 1923.

Upon the Mold Bardic Chair, de Vynk carved women in traditional Welsh dress. This style of outfit originated from 19th century, and was worn particularly by rural Welsh women. The specifics of the style changed with time, but the basics of the dress were bedgowns, shawls, and the iconic tall black hats. Today, you will see girls on St David’s Day wearing red shawls and bedgowns, to identify further with the Welsh culture; however, the 19th-century versions were usually blue, with the shawls having a paisley pattern which originated from India. The traditional Welsh dress itself became very popular due to an increase in the erasure of Welsh culture. People wanted to establish a strong national identity, and many believed that the way to do this was through a national style. Many middle-class women began wearing these outfits worn by farmer’s wives to special events and such, thus popularising the look. At the time there was a lot of tourism in Wales, and so the dress was immortalised in photos, paintings, postcards and ceramics. The version of the dress here is significantly glamourised, (with added lace and frills) but is nonetheless similar to what rural women would have actually worn.

R. Griffiths, ‘Welsh Fashions Taken on a Market-Day in Wales’, 1851.

Image courtesy of Amgueddfa Ceredigion Museum.

The use of wood-carving as a trade turned art form to combine and enrich Belgian and Welsh cultures is a unique situation. However, artistic documentation of displacement is highly important, and seeing how these two cultures merged during a difficult time is a timeless lesson. I think this is very fitting as the entire purpose of the Eisteddfod is not only to preserve Welsh culture but to bring people together through art such as music and literacy, and in this case wood-carving. We have much to gain from these beautiful chairs and the rich history with which they are so elegantly infused.

For more information on Bardic Chairs, take a look here:

https://www.peoplescollection.wales/collections/1546806

Blog Inspiration:

https://www.visitcardiffbay.info/event/unsettled-lives-war-and-displacement-in-wales/