Why ‘Unbound’? Reasons that mysticism and magical art are so significant.

Words by Kordélia Mészáros

Edited by Myfanwy Greene

Sacred art, escapism, fantasy aesthetics, the idea of being crazy but free, feminine intuition, the moon, witches?

Why are we so drawn to mysticism, the occult and the idea of magic? And why utilise art as a medium for these themes?

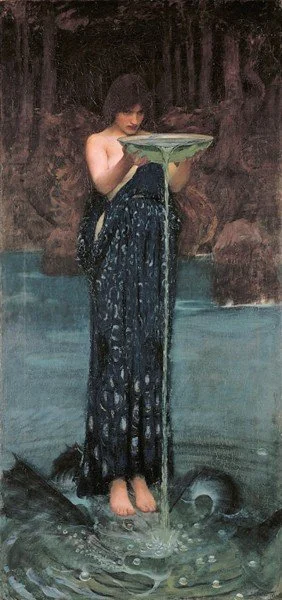

John William Waterhouse, ‘Circe Invidiosa’, 1892.

Trying to understand the world and who you are within it has been a natural experience from the ancient world to our contemporary society. In a way, attempting to reason with the world might be one of the most relevant things of our time. With so much information circulating around us, infinite trends and societal pressure to become something, it feels like an innate response to try to decode meaning from our obscure world. Art can act as an educational tool, but also a cathartic one, to help explore and express who we are.

The usual process of creating any form of art is a sort of magic in itself, as a new, unified whole is made from raw, disassembled materials. Even when using an unconventional process like breaking something to create a new work, resulting in not a literal unified whole, the idea of calling into being and creating something that has previously not existed in its new form holds a mystical essence.

The creative process is also a vulnerable, often intimate reflection of an artist's introspection or an idea they want to communicate. As a spectator, looking at any artwork highlights a part of our own selves. A complex emotional response is invoked, or a feeling of nothing extraordinary, even a simple aesthetic pleasure from an artwork may reveals a part of ourselves or some of our personality.

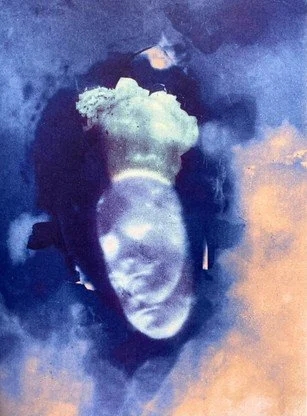

Charles Lacey, ‘Photograph of a Thought’, 1894.

One’s creative process enables you to step away from oversaturated and superficial spaces that often leave you feeling depleted. Attempting to understand the world and our place in it through embracing concepts from an intuitive place feels like a breath of fresh air. The strange uniqueness of a mystical artistic space requires a reflective observation of ourselves, drawn directly from our minds and emotions. This allows us to create a reality that is more connected to who we are and importantly enables us to receive authentic answers more naturally for what we need from life, others and ourselves.

The dismissal of mysticism as ‘juvenile’, in favour of facts and logic, is a common sentiment, yet mysticism occupies significant space in our lives. Despite both concepts being capable of co-existing in symbiosis (often science and the occult, rational and mystical ideas intertwine), mysticism and magic as a means to explore confusing aspects of the world are a freeing and necessary approach for many.

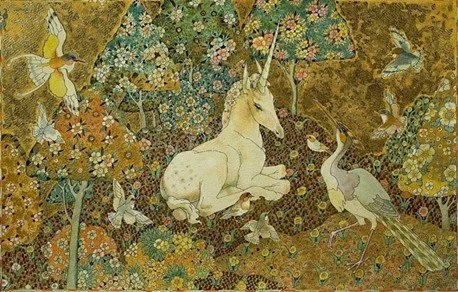

Boris Anikin, ‘A Unicorn in Bloom’, 1947.

From the animated film ‘The Last Unicorn’ (1982) there is a quote,

‘I had forgotten that men cannot see unicorns, if men no longer know what they’re looking at, there may well be other unicorns in the world yet.’

An idea from this quote that can be applied to the arts is that as art still exists, the mystical and magical also still exist. Humankind, in the film, have lost the ability to perceive unicorns, these whimsical, deeply complex creatures, but this inability to see or understand them does not equate to their complete disappearance from the world.

In a way, the idea of not knowing what we are looking at and that causing us to miss what is exactly in front of us, is a strong essence of mystical, magical art. To some, the artwork representing these themes may be meaningless, but to others it provides an important world of safety and authentic expression. The belief in the mystical nature of things creates a sense that there is more to the world than what we experience in any given moment. Art creates a promise of change and understanding, hidden in plain sight.

With the current social and political climate it may appear as if the world is turning bleak with the widespread defunding of the arts and what appears to be a lack of reflective judgment. However the inability to acknowledge the existence and/or importance of things does not mean that they cease to exist.

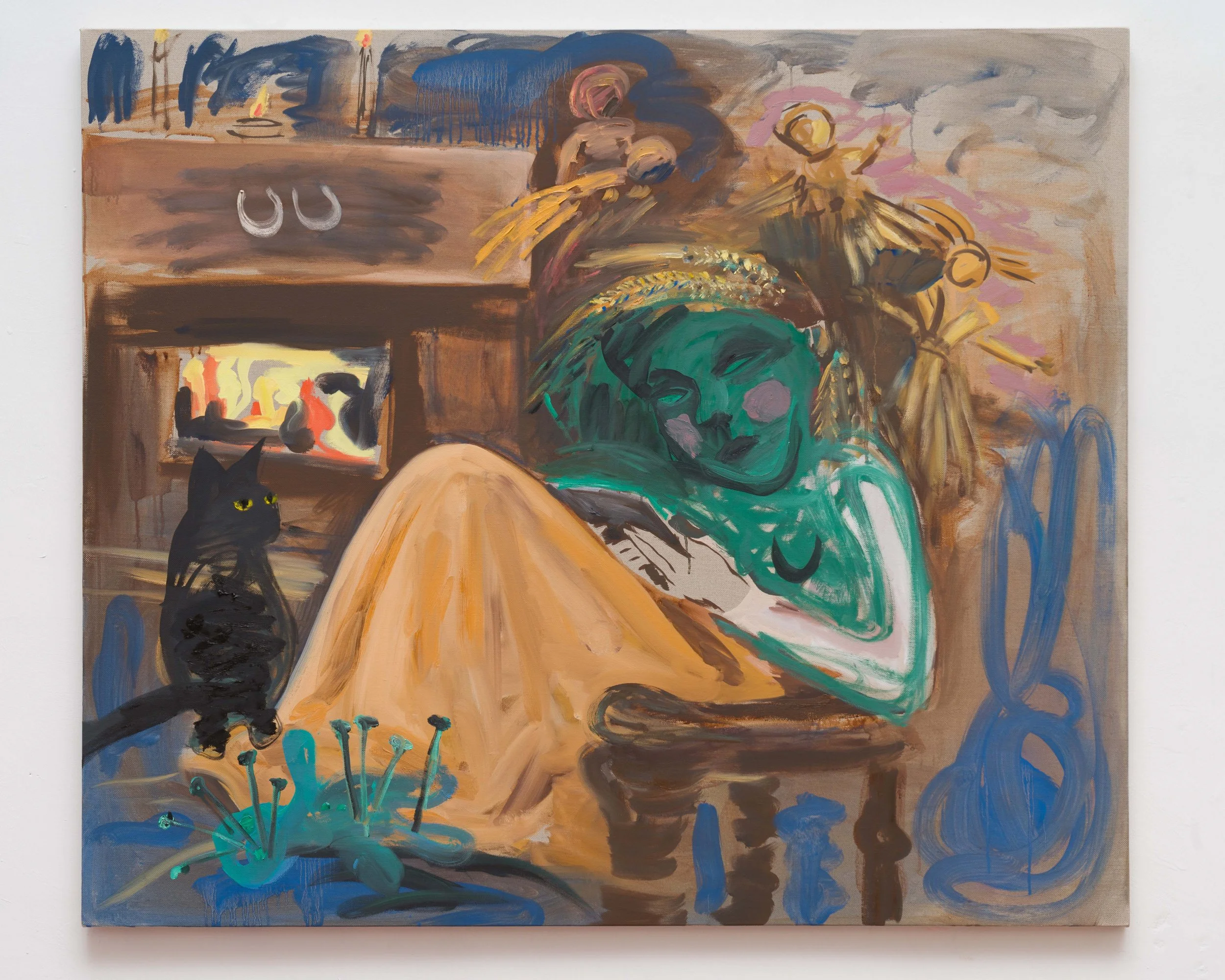

Lucy Stein, ‘The corn goddess goes back on Instagram’, 2021.

Art that reflects these ideas therefore becomes more important than ever. Indeed, as a collective we must reach to create and experience artworks of a mystical, magical nature as a response to a tense atmosphere. Through creating and/or interacting with these artworks we can free ourselves from societal pressure and limiting boundaries. This is especially significant when an individual or group of individuals have felt misunderstood and unsafe being themselves. A limitless environment can be an escape, the idea of a mystical knowledge guiding us to do better or even just feel better, urging us to express our true selves, allows us to feel authentically unbound. Many are drawn to these ideas of mysticism in order to understand the chaos and disorder we experience and to create a network of safety within it.

In her book, The Art of the Occult, S. Elizabeth shares a similar sentiment ‘... that magic and the hope that there is more dreamt than in our familiar philosophies is a vital aspect of the human condition’ and that this ‘... is an especially powerful desire in times of turmoil and upheaval… [and] during times of uncertainty…’ Therefore, mysticism, magic and the occult in art propose a way through which the world can become malleable.

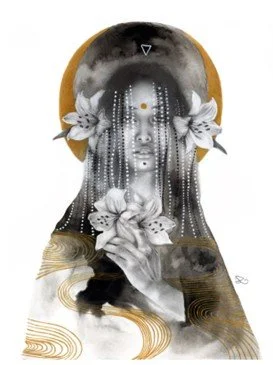

Patricia Ariel, ‘Four Elements: Water,’ 2018.

Art becomes the medium or the ‘looking glass’ with which we can access eclectic perspectives about our place in the world. Furthermore, more than just accessing these ideas of mysticism, art of the magical and ‘occult’ genre allows us to better understand our emotions, our reactions and interactions with different themes and ideas separate from our own. It urges us to decenter our rigid beliefs and embrace foreign concepts.

Many of these can appear strange, lacking rationality or logical explanations but ultimately they allow us to embrace ideas that seem ephemeral in our overwhelmingly fast-tracked world.

————————————————————

References:

Elizabeth, S. 2020. Art of the Occult: A Visual Sourcebook for the Modern Mystic. N.p.: White Lion Publishing.

Rankin Jr., Arthur, and Jules Bass, dirs. 1982. The Last Unicorn.