Artist Interview with Georgina Lingard

Interview by Charlotte Whitehill

Edited by Myfanwy Greene

Following the success of the opening night of Unbound at The Norman Rea Gallery, I sat down with mixed-media sculptural artist Georgina Lingard to chat all things unbound! Georgina is a graduate of Manchester Metropolitan School of Art. She works with woodwork, metal and found objects to create outstanding mixed-media sculptures.

Here is Georgina Lingard, in ten questions:

Georgina Lingard.

Charlotte: You suggest that artists are a conduit for expressive communication, using their artworks as an offering to audiences. How does this idea develop the way you create your structures?

Georgina: Yes, I believe all artistic expression is an offering of self, skill and time, leading to a tangible, devotional outcome. In my own structures, I’m deeply aware of the vulnerability involved in turning inner expression into a physical entity. I want it to speak back to me that it has embodied its own journey. And I see this as a sacred procedure, much like Process Art, where creation itself is the driving force. As a conduit of my craft, I pour myself into the making, obsessively reworking until something clicks. The final piece becomes a testament to this intuitive yet mechanical approach, one that often surprises me. It’s as if the work has revealed a logic that I wasn’t fully aware of.

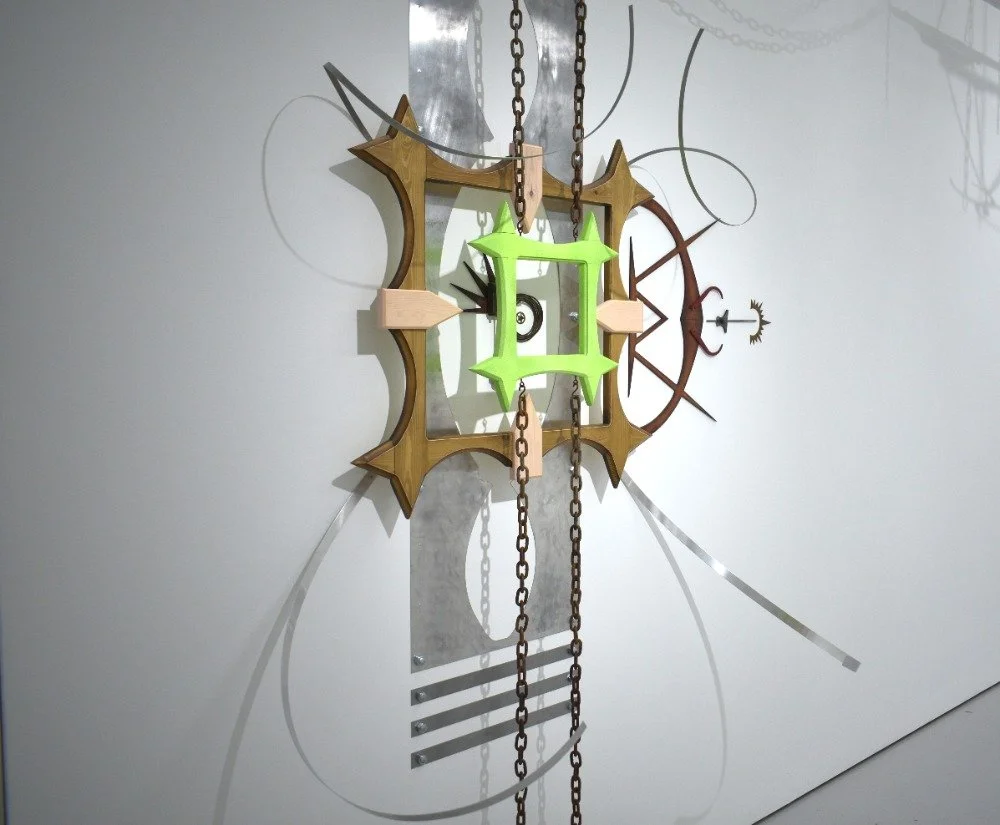

Georgina Lingard, ‘Codex Machina’, 2025.

C: You often use wood, metal, and found objects when creating your works. What draws you to these materials and what role do they play in your sculptures?

G: As an artist I wanted to find a skill I could hone. Dedicating time and practice in the solitude of the wood shop gave me the initiative to level up my sculptures. I found the progression deeply spiritual, and there is something extremely satisfying about bringing a concept into fruition. Therefore, the medium and the machinery that aided this pursuit became the product of my fascination. I sketched the forms of hardware into my designs, both depicting them in a new light of worth and breaking the illusion of art until I, the labourer, was visible within. The incorporation of metal and authentic tools allowed my handcrafted woodwork to feel rustic yet industrial, and functional despite their undisclosed use. The aesthetics of function is my main goal, to transcribe the bones of process and the fragmented remnants of construction. Wood, metal and found objects are not just material, but are symbolic of the skill, industry and identity that I am reaching toward.

Georgina Lingard, ‘Codex Machina’, 2025.

C: Many of your works explore the intersection between the sacred and the industrial. What interests you about this mix between the handcrafted and the mechanical?

G: They feel to be oppositional, artisanal versus capitalism. But as artists working a profession, we sit precisely at that intersection. Our handcrafted goods offered up to the consumer as devotional offerings of our greatest care, and yet still they must enter systems of demand, supply and industry. In my practice I often feel akin to a machine, steadily producing, thriving under pressure and driven to make before the idea slips away. There is peace in having this functionality, which I believe can be attributed to the taboo association between productivity and worth. It is still, however, the closest I’ve come to feeling a divine purpose, and I long to keep the flame alive. But there’s also fear of burnout, and so my interests lie in this fragile balance of how machinery can both support and expose our limits. To reflect on the contradictions between invention and creativity, function and worth. The candle burning at both ends, but in the glow confronting that paradox, something sacred is revealed.

Georgina Lingard, ‘Codex Machina’, 2025.

C: Forgotten tools and old machinery often appear in your work. How do these objects change once they become part of your sculptures?

G: Firstly, you could argue that their vitality has been ‘killed’, an idea Fiona Candlin discusses in her book Micromuseology. These objects have been displaced from their original function, and by incorporating them into non-functional artworks I have altered their status. For, if they are not being used for their intended purpose, does not the power within them die? I set out to argue that if objects are assigned their purpose based on their use and environment, we as the users have the authority to transform them. These old tools and fragments of machinery carry the marks of their past lives, worn but once useful, now abandoned in car boots as relics with a half-forgotten purpose. I aim to give them a second life and use them incorrectly in order to defamiliarise their image and uncover something unknown. In my sculptures, they become artefacts of the act of making. A museum of past intention now lifted by the ritualised process of creation, and the ritualised looking performed by the viewer. In turn, the vitality of my sculpture is dependent upon the components that give them a feeling of authenticity. A sense that a mechanical meaning exists within, and its discovery will be found in my misuse of things.

C: Unbound explores the mystical and the magical. Do you see your own process of making and assembling as a kind of ritual or alchemy?

G: Undoubtedly. I believe that the act of making and assembling is deeply aligned with both ritual and alchemy. Ritual refers to a sequence of actions carried out methodically and instinctually, much like every artist’s unique practice — shaped through repetition and refined instinct. To make art is to step into the mindset of creation and willingly surrender to that creative force. To engage in a dialogue with a strange, ancient form of expression. A ritual-like practice passed down for centuries that is infused with memory, symbolic intent and the search for meaning. Alchemy, on the other hand, speaks to transformation —turning base matter into gold. I imagine that when I am making, the creation of a thing that once did not exist holds a mystical charge. Through intention, labour and belief, I turn material into thing, objects into mechanisms, and if I consider the process to be one that is spiritual, am I not actively imbuing them with a sense of sacredness that transforms their worth? Do we not all, as artists, decree our manifestations to be something more than they were before? This significant alteration has allowed us to attest our work to be art, in the hope that to someone else it will be gold.

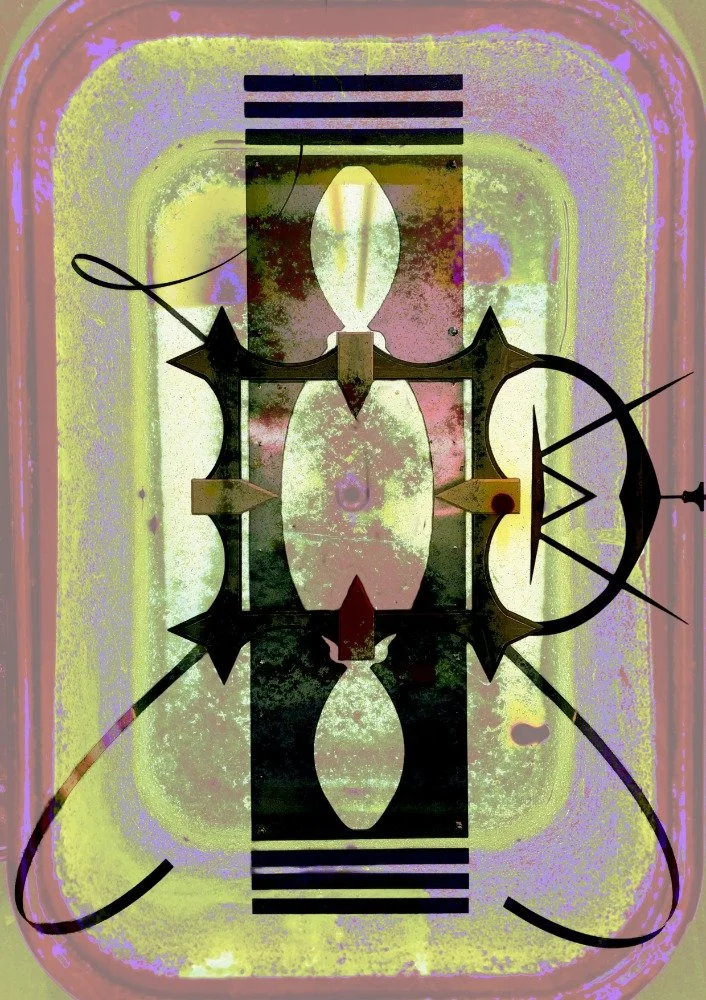

Georgina Lingard, ‘Vestige Machina’, 2025.

C: Your sculptures often resemble relics from unknown belief systems. Do you intend for them to feel like fragments of forgotten rituals, or inventions of entirely new ones?

G: I think they exist somewhere in between, and I enjoy that the viewer can project their own meanings onto them. What matters most is that the sculpture feels significant, like a fragment of something once vital. Their forms suggesting use, ceremony and intention but without a clear origin. The rusty chains may hint to dilapidated decay, whilst the polished metal argues that the thing is still being tended to. By combining the handcrafted with industrial remnants, I create amalgamations that feel both ancient and futuristic. Seeking to explore the untethered space we find ourselves in when we cannot accurately decipher a system. The freedom of speculation, of discovery and of invention.

C: This exhibition looks at how art can disrupt and challenge fixed ideas and propose alternative worlds. In what way does your work invite audiences to reimagine or re-enchant the everyday?

G: Once my sculptures have come to life, I want them to emit a sense of spiritual ordinance. Inviting a feeling of awe and sacredness. When we have access to a multitude of wondrous sights on a daily basis, we forget what it is that makes them enchanting. Through my work, I seek a creatively-driven, quasi-religious experience. Enchanted by the act of making, the nature of being an artist and of my environment that is full of inspiration. I hope viewers are prompted to see art in the everyday, in the arrangement of a dressing table or a mantelpiece of cherished keepsakes. My sculptures celebrate that same impulse, to be led by a creative spirit. To enrich the mundane that then in turn supplements our lives.

C: There is a sense of loss and longing in your installations, machines with unclear functions and tools without an obvious purpose. What do memory, absence, and mystery play in your practice?

G: I’ve always been drawn to the occult; concocting potions, arranging altars, bottling and hoarding and imagining. But growing up I suppressed that instinctual way of being, one which was was greatly intertwined with my creative self. I was told art had limited worth, that money mattered more, and that my soft pursuits were a weakness to success. After confronting the death of my dad at twenty years old, I eventually returned to art as a reclaiming of the identity I’d left behind. Now my practice merges ritual, grief and the creative play of assembling fragmented things in a search for my own purpose and function. My sculptures become time-capsules, these symbolic markers of memory, absence, and the longing to make something whole. They honour both my past and the lost and abandoned objects I restore. Acting as a reminder of how I make art, and of how I view all things in the light of worth. That the ritual of making is always purposeful, and always functional, even when its value is obscure to others.

Georgina Lingard, 2025.

C: The Norman Rea Gallery prides itself on giving visibility to experimental and emerging practices and local artists. How important are these platforms for artists working on the edges of the art world?

G: They are vital. Artists depend greatly upon platforms that can provide wider reach and deeper engagement. Without them, many creatives remain trapped in an echo chamber of their own environment, isolated by circumstance and constrained by limited opportunities. For those working on the edge of the art world, it is the difference between access and stagnation. Art also holds a subversive quality, challenging norms and provoking thought. Platforms such as The Norman Rea help to uphold this core identity of the creative field. Giving a voice to those just emerging, those underrepresented and those who want to break norms. To be new, innovative, and unconventional. A cycle that supports an artist’s visibility ensures their validation can continue and shapes the art world to become a diverse and dynamic landscape which, in turn, encourages others to take up the mantel.

C: And finally, if you had to describe your artwork in three words, what would they be?

G: Numinous, amalgamations and genesis.

Georgina’s sculptural installation ‘Codex Machina’ will be exhibited at The Norman Rea Gallery in Unbound, running from now until Friday 17th October 2025.