‘The Omnipotence of the Dream’: The Surrealist Manifesto of 1924

Words by Myfanwy Greene

‘I am defining it once and for all:

SURREALISM, n. Psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express – verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner – the actual functioning of thought. Dictated by the thought, in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern.

ENCYCLOPEDIA. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life. [. . .]’

André Breton’s 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism

André Breton, 1924.

When I first came across André Breton’s Surrealist Manifesto of 1924, I was struck particularly by the idea that Surrealism sought to express the ‘true function of thought’ and ‘the omnipotence of the dream.’ In an era in which the arts were increasingly influenced by the growth of psychoanalytic theory, this desire to understand and portray the inner workings of the mind resulted in some fascinating works. Although Surrealism was by no means limited to painting (it spans across poetry, theatre, sculpture, literature etc.) I will specifically be looking at paintings here. Breton argued that man was no longer content with his destiny, and the only way to maintain the lucidity that gave life meaning was to emphasise the value of childlike perception, continue to question the line between dream and reality, and oppose realism and logic (both of which he viewed as repressive).

Paul Klee, ‘Prestidigitator (Conjuring Trick),’ 1927, The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Let us begin by having a look at Paul Klee’s 1927 painting ‘Prestidigitator (Conjuring Trick).’ In accordance with the Surrealist Manifesto, there is a distinct opposition to realism. Initially, our brains sift each of the various shapes in Klee’s painting into categories that we recognise in our daily lives. The shapes in the middle of the painting appear to come together to form a face, perched above what we might recognise as a table. The triangular formation off to the bottom left reminds us, perhaps, of a set of stairs, as the six quadrilaterals to the left of the face remind us of a window. Directly above the face, there appears to be some sort of lamp, which illuminates the scene below. The Philadelphia Museum of Art notes the ephemerality of this piece, which, they argue, pulls the viewer ‘into spaces of fantasy and imagination.’ The sparsity of the scene allows space for our minds to wander, and yet we are still grounded by some sense of the real, which Breton valued as one of the key aspects of Surrealism. ‘Beloved imagination, what I like most in you is your unsparing quality,’ Breton wrote. Klee’s painting, while formally somewhat spare, is undoubtedly unsparing in its room for interpretation and surrealist enjoyment.

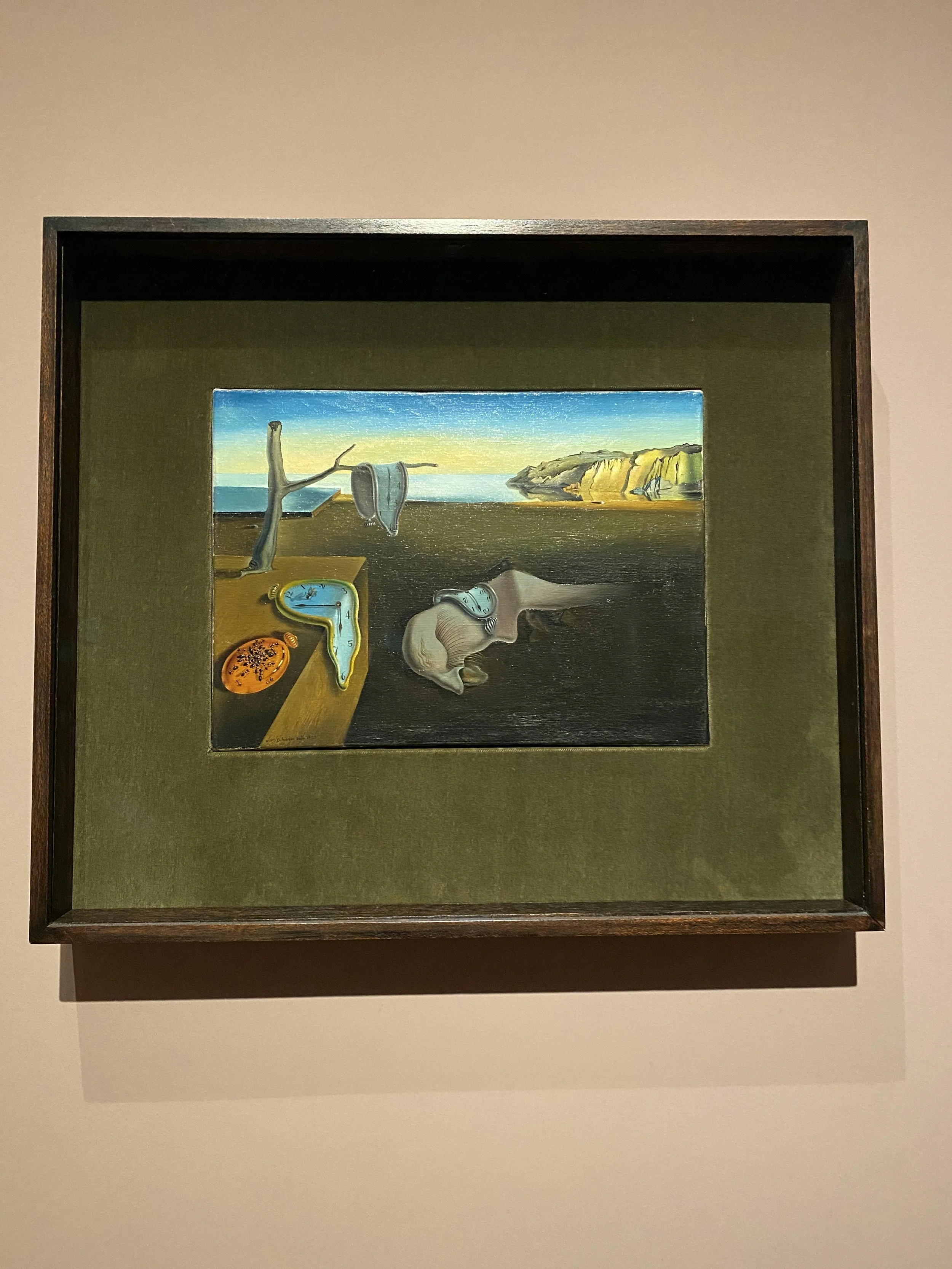

Salvador Dalí, ‘The Persistence of Memory,’ 1931, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Perhaps the most recognisable piece of Surrealist painting is ‘The Persistence of Memory’ (1931) by Salvador Dalí. Initially, as with Klee, we recognise the elements of the real – the clocks, the bare tree, the cliff, the horizon. As our brain kicks into gear, these elements begin to stray further and further from the reality that we know. The tree grows from what appears a solid block – how is that possible? The clocks are limp and lifeless, and why are they all telling different times? The foreground is dark, and yet dawn appears to be breaking over the horizon, splaying the cliffs with morning light. Dalí has created a fascinating dreamscape, where things we appear to know and recognise manage to wander beyond our notions of reality. Breton’s manifesto emphasised the dream and our sub/un-conscious states, questioning why more credence was given to waking events than events occurring in the dreamscape. He lamented, ‘the dream finds itself reduced to a mere parenthesis, as is the night.’ Like Breton, Dalí places emphasis on the dreamscape, encouraging us to critique our own notions of reality, and seek out meaning in the parts of our lives deemed ‘less’ than reality. Who’s to say the dream is less real than the waking moment? This question confronts us.

Man Ray, ‘Fair Weather,’ 1939, The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

‘Fair Weather’ (1939) by Man Ray, which he described as the culmination of his Surrealist career, is a masterpiece of Surrealism, heavy with imagery and symbol. It fits into the Surrealist-coded dreamscape, but this time in a slightly darker sense than perhaps the previous two paintings we have seen. The Philadelphia Museum of Art describes it as ‘a nightmarish premonition of the Second World War.’ Ray has included symbols of violence which give the vibrant painting its undeniably dark background. The wall is damaged, blood drips from the door’s keyhole, accumulating in a puddle on the floor, while two mystical animals fight each other on a roof. Ray’s painting reveals the darker side of Surrealism, the nightmarish, the facets of human nature that we do not like to face – violence and war. Breton asks, ‘Can’t the dream also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life?’ Man Ray’s painting alludes to our human shortcomings, forcing us to react and begin questioning them.

Kay Sage, ‘Tomorrow is Never,’ 1955, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Finally, we turn to Kay Sage’s haunting painting ‘Tomorrow is Never’ (1955). One of the later pieces in the Surrealist art movement, Sage’s work has a distinctly ominous, fleeting quality about it. It is a dark piece, grey in tone, with structures emerging from what seems to be a heavy mist. Within these oppressive structures lie more delicate, free forms. The Met has described this piece as a ‘metaphor for the mind and psychological states of being.’ They also note the themes of ‘entrapment and dislocation’ that the piece evokes. The forlorn, pessimistic title reminded me somewhat of a quote from the manifesto – ‘Everything is Elsewhere.’ Both quotes, especially when placed alongside one another, remind us of the Surrealist mantra to look beyond what appears at face value, and continue to explore the many caves that our brain desires to explore. Balancing cynicism and frivolity, the Surrealists encourage the viewer down paths to new answers and onto deeper exploration of life’s mysteries.

These Surrealist paintings urge close looking, a process which, in itself, draws the viewer in and forces us to confront symbol, colour and shape in such a way that we are left questioning both the external processes of our modern world, and the internal workings of our consciousness. The Surrealists invite us to look, and then dare us to look again, and continue looking, locking us in a perpetual examination of the world and its infinite puzzles. I’ll leave you with a final Breton quote to think about, so that you may spend the next few moments musing on the Surreal.

‘I am growing old and, more than that reality to which I believe I subject myself, it is perhaps the dream, the difference with which I treat the dream, which makes me grow old.’

Keep dreaming.

——————————————————————————————————————————

Sources:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Breton, André, ‘Manifesto of Surrealism,’ 1924.