Constructing Queer Historiography: The Case of Karol Radziszewski

Words by Ania Kaczyńska

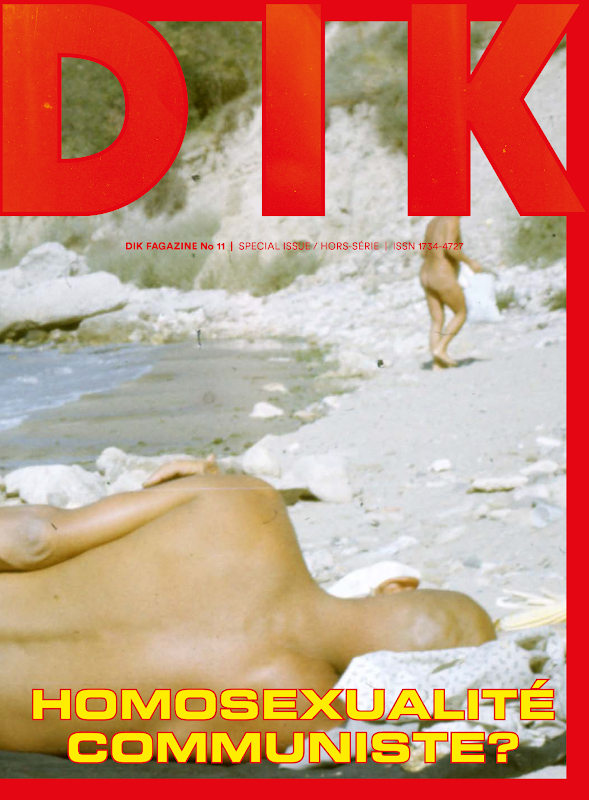

Cover of DIK No. 11, 2017 Bilingual (English-French) issue: Homosexualité communiste?

Among the hegemonic archival-historiographic practices, the history as we know it continues to lack a sufficient representation of queer people; the narrative that they have not existed still prevails. To construct a queer historiography (and queer archives) means to restore the memory of the repressed past and find new ways to understand both memory and legislation, as well as provide a framework for understanding contemporary life. It is this kind of queer heritage and its archivisation that emerges from the artistic practice of a Polish artist Karol Radziszewski.

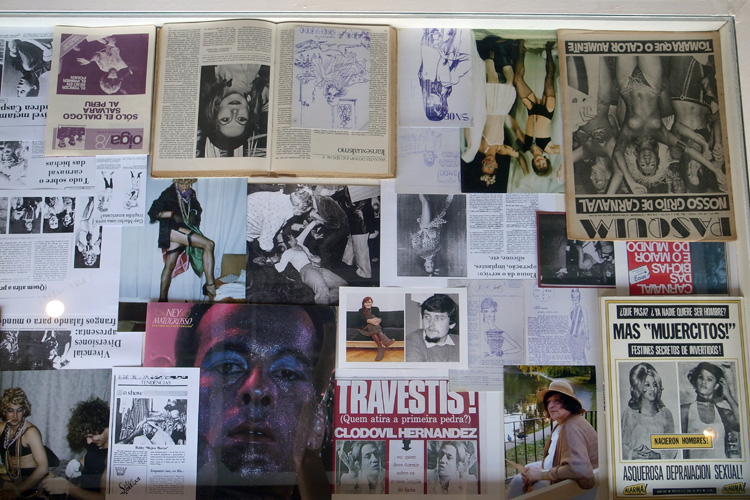

Queer Archives Institute. Photo: Culture.pl.

Karol Radziszewski (b. 1980) has been working on preserving Polish and Eastern European non-heteronormative histories for almost two decades. Through appropriation and reinterpretation, the artist consciously uses neo-avant-garde art practices as a starting point for his very own queer narratives. Although he is not a historian, a huge part of his practice involves historiography, heritage and the archive: these emerge as main themes and methods of his works.

Karol Radziszewski, covers of DIK. Photo: Culture.pl.

Radziszewski’s projects focused on the so-called ‘queer archives’ including DIK Fagazine, a journal founded in 2005 focused on homosexuality and masculinity sought to locate homosexuality within the context of post-communist Eastern Europe. It combines contemporary art practices with archival research and preservation of the past. It is, so far, the only publication of the sort in the region. Although it was founded with intent to focus on queer art on a global scale, it has since evolved to focus on Eastern European queer art, its archivization and historiography, which require a different approach compared to the West. As part of the project, Radziszewski travelled from Poland to some of the Eastern European countries (Ukraine, Belarus, Croatia, Romania, to name a few) recording local queer histories (from love stories to anecdotes of homophobia) and collecting tons of material. The most recent issue (from 2017, since the journal is currently on hold) is a monographic issue on Belarus. The artist is interested precisely in what has been excluded from heteronormative history in order to restore it and, in turn, re-produce queer version of that history.

Queer Archives Institute, exhibition view at Videobrasil, São Paulo, Brazil, 2016. Photo: Everton Ballardin.

Queer Archives Institute (QAI) was founded to accomodate the large amount of material Radziszewski has been collecting for DIK Fagazine (now being its official publisher), as the archive he created often went beyond what he could actually use in a journal. It is a non-profit organisation founded in 2015 dedicated to research, collection, exhibition and analysis of queer archives from the region. It has since become the centre of Radziszewski’s artistic practice against a backdrop of increasing hostility towards queer individuals from the state and nationalist groups. Creating a reservoir of non-heteronormative experiences and producing queer heritage emerges as especially important in the light of increasing polarised debate surrounding the rights of queer communities in Eastern Europe (and beyond). The most recent example is Radziszewski’s solo exhibition One Day These Kids… (10 February–15 April 2023) at the Between Bridges foundation in Berlin, Germany, in which the artist conceived an expansive site-specific installation alluding to a conventional 1990s Polish classroom, appropriating its visual language (which traditionally excludes queer narratives) and reconstructing nation-state-based cultural heritage.

Installation view of Karol Radziszewski: One Day These Kids… at the Between Bridges, Berlin, Germany. Photo: Wolfgang Tillmans / Between Bridges.

Activities of Queer Archives Institute aim to resonate mainly within the framework of the Western world, beyond the region of origin, acknowledging the specific relations and differences between the Western and Eastern Europe. But they are also a personal and local collection of memories completely distinct to the North American/Western European contexts which redefine queer identity, reality and experience in Eastern Europe.