Beyond Koi Fish on Pinterest: The Complex Cultural History Behind Japan’s ‘Irezumi’ Tattoo

Words by Amelie Griffiths

Edited by Myfanwy Greene

Perhaps one of the most commercialised aspects of the artistic world, the art of tattooing is often greeted at a surface level, especially in the Western world. Reactions to the commodification of tattoos are somewhat polarising, as it has no doubt allowed for greater acceptance of those with body art and accessibility to receive it, as well as to make a living from doing it. On the other hand, cultural significance and symbolism is often lost as a result, uprooted by the growing trend of aestheticism.

While I am personally all for the increasing exposure of tattoos, I believe that some styles should be regarded with a special kind of reverence for their deep and complex traditional history; one of these styles being Irezumi, a longstanding and distinctive Japanese style which dates back to the 16th century, otherwise known as the Edo period.

My research into Irezumi began when I first started scouring the internet for tattoo ideas on Pinterest, with that same excitement many young first-timers feel where they would have anything tattooed on themselves – in an utter haze of eager, adolescent rebellion – as long as it’s visually pleasing enough. I saw a linework tattoo of two koi fish circling each other, in red and black, and thought it was pretty. So I haphazardly searched its symbolism, in the hopes that Google would conjure up something of amazing depth – something that would complete a jigsaw puzzle in my mind that even I wasn't aware of yet. Determination, resilience, personal growth, Google explained. I scrolled some more and found that the imagery stemmed from some kind of traditional Japanese style. Cool, I thought to myself, and left the information untouched, like dipping your feet into the shallow of the sea and never daring to venture further.

Tattoo by @vvinkxo on Instagram.

But this brief encounter with the vast expanse of Japanese tattoo artistry didn’t really do it justice. One of the most traditional and standout styles happens to be Irezumi, translating quite straightforwardly to ‘insert ink’ in English.

The first evidence of tattooing in Japan dates back to 5000 BCE, where it was initially created with the intent of purely decorative purposes. However, this eventually morphed into a way to brand and distinguish criminals in prison establishments. This method of tattooing further led to an unconscious distinction between social classes; those with punitive tattoos were viewed by others – with either conscious or unconscious bias – as lower class, and often feared and ostracized.

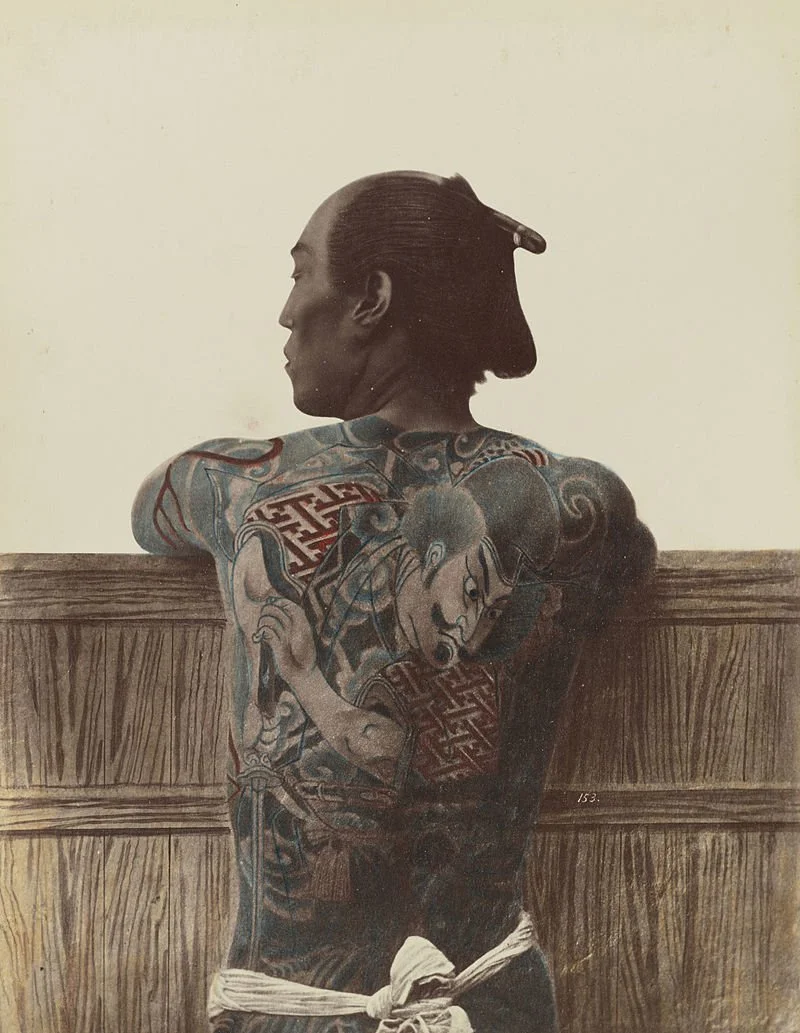

Kusakabe Kimbe or Raimund von Stillfried, Japanese Tattoo, between 1870 and 1899, hand painted albumen silver print.

https://inkhappened.com/japanese-snake-tattoo-hebi/

Irezumi’s popularity would continue into the early 1800s, where they were also used as a decorative way for ex-prisoners to cover up previous markings. It was an attractive way for people to be able to physically embody new beginnings – one of the most persistent figures, the ‘hebi’ (snake) symbolised rebirth and transformation, and so was the perfect incarnation of this.

Other figures present in Irezumi – such as the ‘kirin’ – had ties to Japanese folklore and figures of the underworld. ‘Kirin’ consisted of the body of a deer, head of a dragon and scales of a fish, and represented a wise leader. It was a rare tattoo to receive by an Irezumi artist, with designs being chosen for you rather than one seeking them out. This sense of individuality – chosen not by the receiver but by the artist themselves – contrasts greatly with modernised western tattoos, where customs are frequently made to aesthetically and symbolically suit said tattooed person. The tradition of a customer being oblivious to their tattoo’s design until it is completed continues in Japan today.

Stacy McCleaff, Blue Kirin, tattoo.

The Meiji period, (1868 to 1912) led to the westernisation of Japan, and as a result, the censoring of traditional Japanese tattoo styles. Japan’s government became concerned with self-presentation following an increasing Western interest in their culture, and began to view permanent body art as wholly barbaric. This led to an official government ban on tattoos. Resulting in increased efforts made to cover tattoos, the practice of Irezumi would fade into the shadows, hidden away.

Despite the ban, there is still some evidence that suggests that the practice of Irezumi wasn’t completely erased, but continued away from the eyes of the government. Prince George (King George V) was said to have received Irezumi whilst visiting Japan in 1881; the ban wasn’t lifted until the 1940s. If figures of such high status were still able to successfully locate Irezumi masters, this suggests that the ban didn’t completely erase its relevance and history.

Luke Fildes, King George V (1865-1936), 1911-1912, oil on canvas. The Royal Collection.

While lifting the ban on tattoos should have been celebrated by artists, the Japanese instead regarded it with a skeptical eye, as the raising of the ban was suggested by American settlers rather than the government. The lifting of the ban also meant the globalisation of traditions such as Irezumi.

While this was positive in terms of global exposure, less global emphasis was placed upon the cultural and historical aspects than the visual phenomenon of an intricately crafted full-body piece.

When components of Irezumi are taken out of context, and used for their visual aestheticism in contemporary western societies – such as the koi fish I saw on Pinterest, which remains a popular choice today – we continue to lose the heritage of Irezumi.

Fortunately, there are a few considerable artists who have kept the tradition alive, and who draw attention to the meticulous process of its design. Perhaps one of the most famous is Horiyoshi III from Yokohama, who continued to use the traditional method of ‘tebori’ to apply Irezumi to the skin up until 1985. The method consists of using a wooden or metal stick with needles attached to the tip, and allows more vibrancy in the outcome of colour, especially bright red, which is implemented often in the practice.

Portrait of Horiyoshi III in Hypebeast interview.

Horiyoshi also co-owns an unusual tattoo museum with his wife, which displays full-body Irezumi on skin willingly donated after death (The Museum of Tattooed Skin, Tokyo). This is just a small segment of the rich history which supports the backbone of the entire tattooing industry, and calls for it to be taken seriously as an art form. I have certainly learned to appreciate tattooing beyond merely looking at koi fish on Pinterest. By paying attention to the stories behind the ink, we can continue to destigmatize tattoos and gain a greater appreciation of their immense beauty and heritage.

Research Links:

Tattoos in East Asia: Conforming to Individualism

Irezumi: Tradition and Criminality

“Irezumi”: The Japanese Tattoo

An Intro to The Mythological Creatures of Japanese Irezumi

https://www.widowtattoo.com/blog/horiyoshi-iii

https://cvltnation.com/dead-skin-living-art-the-museum-of-tattooed-skin/